In all my years of making art, there’s one question that never ceases to come up: “Why is your work so expensive?”

I set the price of my work based on the amount of time it takes me to complete it. Of equal importance is the quality of the materials I use in its creation and, most importantly, the years of education and the hard work I have invested in honing my skill to a highly refined level. The amount of effort that goes into creating a piece of work from start to finish is something that most people misunderstand. Let me explain to you how that works.

When I graduated from art school, two things were at the top of my list: selling my work and having my work seen. Unfortunately, this desire left me open to every cheapskate imaginable. These tacaños all possess one quality: they never want to pay full price – EVER. They always have a reason as to why they can’t do it, “My car needs a brake job, and I can barely afford it, but I seriously want to buy your drawing. Can you lower the price?” “My daughter’s birthday is coming up – I can make the first payment now, and I’ll pay you off when I get my next paycheck?” Whatever. When you’re fresh out of college, these occurrences are a given – you will encounter these shameless lowballers and grifters. They’re unavoidable – sort of like roaches.

And if they didn’t want a discount, they wanted free work! Whether it’s a logo or a portrait of their mother, sooner or later, someone’s going to hit you up to work for free. The general public’s reasoning for their brazen expectation for free work is always the same: “It’ll be good exposure.” These fine folks are all, as my mom used to say in Spanish, “Como el azadón,” which roughly translates in English to, “Like the hoe.” A hoe pulls things in one direction, just like a grifter pulls everything toward himself. They take advantage of you when you’re young, optimistic, and fresh out of school. In the beginning, you do your best to overlook this nonsense because you want to sell your work, but after a while, it gets to be a bit much, and your patience starts to wear thin. No one who has worked for years to hone their craft likes getting hit up to do free work. FYI, such actions and expectations will automatically put you at the top of any self-respecting artist’s shitlist lickety-split.

Even now, people continue to ask me about my pricing. After a while, it starts to really gall me. I often wonder if the people who ask me this question ask doctors, lawyers, or plumbers the same thing. Doctors, lawyers, and plumbers charge for their work based on things like education and experience, and no one ever bats an eye about it, but when it comes to art, it’s a whole different thing. Why are people always so skeptical when it comes to the price of artwork? They always seem suspicious of price and never seem to understand why a piece of work is “so expensive.” It doesn’t matter how well-crafted something is – they’re still going to be suspicious. All too often, people want to haggle about the price of the artwork in question and talk about getting a better deal. These fine folks are not subtle in their approach – they’re brash as hell, and they don’t give a damn. I’ve had people tell me they’ve seen art similar to mine at the fucking flea market. Sometimes I feel like a used car salesman trying to sell a Jaguar to someone who wants to pay as if they were buying a Gremlin. It gets old. My patience for cheapskates, bargain seekers, and lowballers is gone. I’ve done my share of charity handouts over the years. Never again.

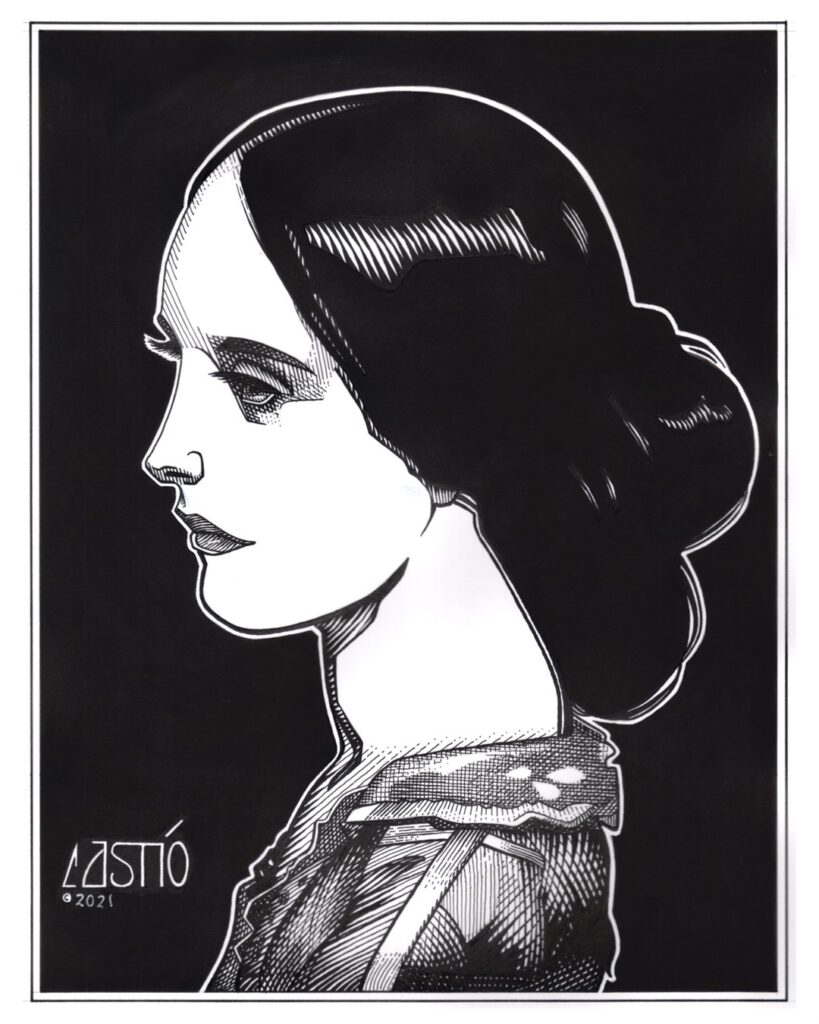

The general public’s bewilderment with price isn’t anything new, and it’s likely not going away anytime soon. Being well aware of this, I’ve decided that this would be a good time to point out the fine details of why a piece of work is “so expensive.” The piece that I’ll be using as an example is a pen and ink study of Carmen Aguado, Duchess of Montmorency, after the portrait by German painter Franz Winterhalter that I’ve produced in preparation for a more extensive drawing of Madame Aguado. My study is a 9″x12″ pen and ink drawing on paper. Not only do I plan to use this study to complete a larger, finished drawing, I will also be selling this gorgeous piece individually. My portrait of the Duchess of Montmorency is small and straightforward in approach, but don’t let that fool you into thinking that those things, or the fact that I completed it in my studio journal, will lessen my asking price of $1200.00. Here’s why.

Firstly, a project like this takes longer than you think. This piece took me, from start to finish, close to twenty-five hours to complete. Twelve hundred dollars may seem like an exorbitant amount of money for a drawing, but if you do the math, you’ll realize that my time comes out to a paltry forty-eight dollars an hour. At that price, I’m practically giving away this fabulous piece of work. Great drawings result from accumulated knowledge and great skill; as with every new project, this study started with a solid preliminary pencil drawing. This sketch is the foundation of everything that will come afterward. At this stage, I need to work out certain things in a very exacting way. A small error in something like proportions at this stage can become a huge problem later. Spending extra time at this stage pays off later. My time is valuable, and I cannot afford to waste it by making foolish mistakes. Once I’ve worked up my initial drawing to where I’m happy with it, I make a tracing of it and continue refining it on tracing paper. When I complete this, I will transfer my drawing back into my studio journal and work out any last-minute details before moving on to the best part: drawing in ink. I would never consider moving on to this final stage if I felt unsatisfied with my preliminary drawing. Every i has to be dotted, and every t has to be crossed before I begin drawing in ink.

For me, drawing in ink is the most enjoyable part of doing this type of drawing. Once I get to this stage, I’ve already done all the hard work and figured out things like proportions, values, likeness, et cetera in my preliminary drawing. Now it’s time to bring my pencil drawing to life; I do all my ink drawing with a Rapidograph technical pen. Rapidograph pens are refillable pens infamous for their non-flexible points; this unavoidable fact forces me to ink my pencil lines twice or thrice to get variety in my linework. In years past, I used to use a crow quill pen to do my ink work, but using a traditional dip pen requires waiting for the ink that flows from the nib onto the paper to dry, which takes up time. There is none of that when you use a technical pen; it’s why I lean so heavily on Rapidographs for my work.

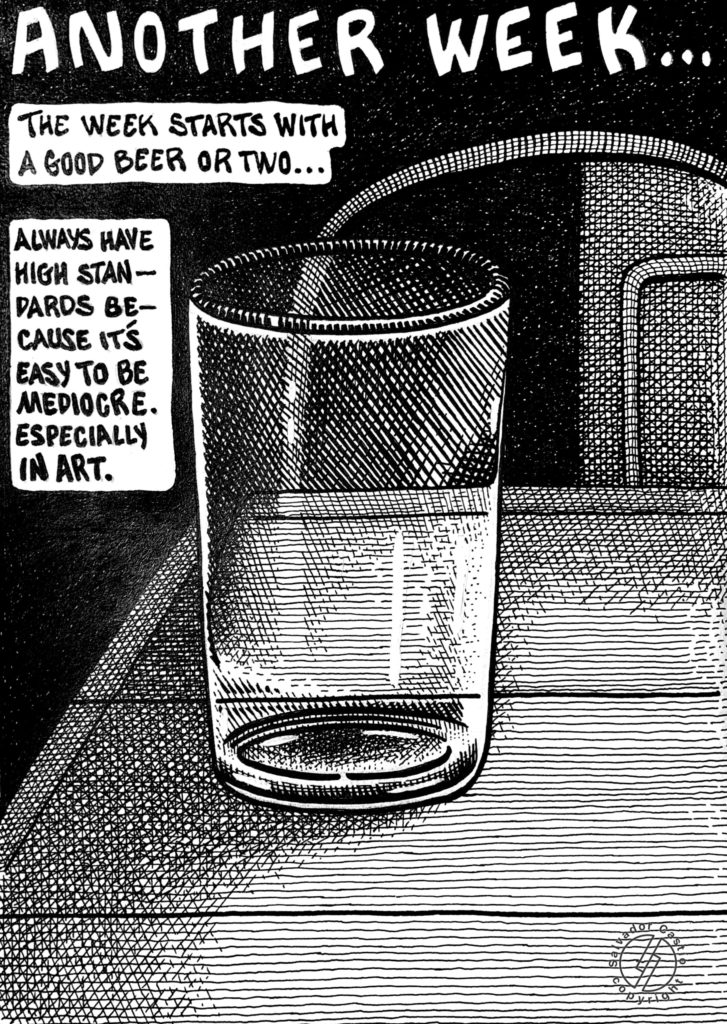

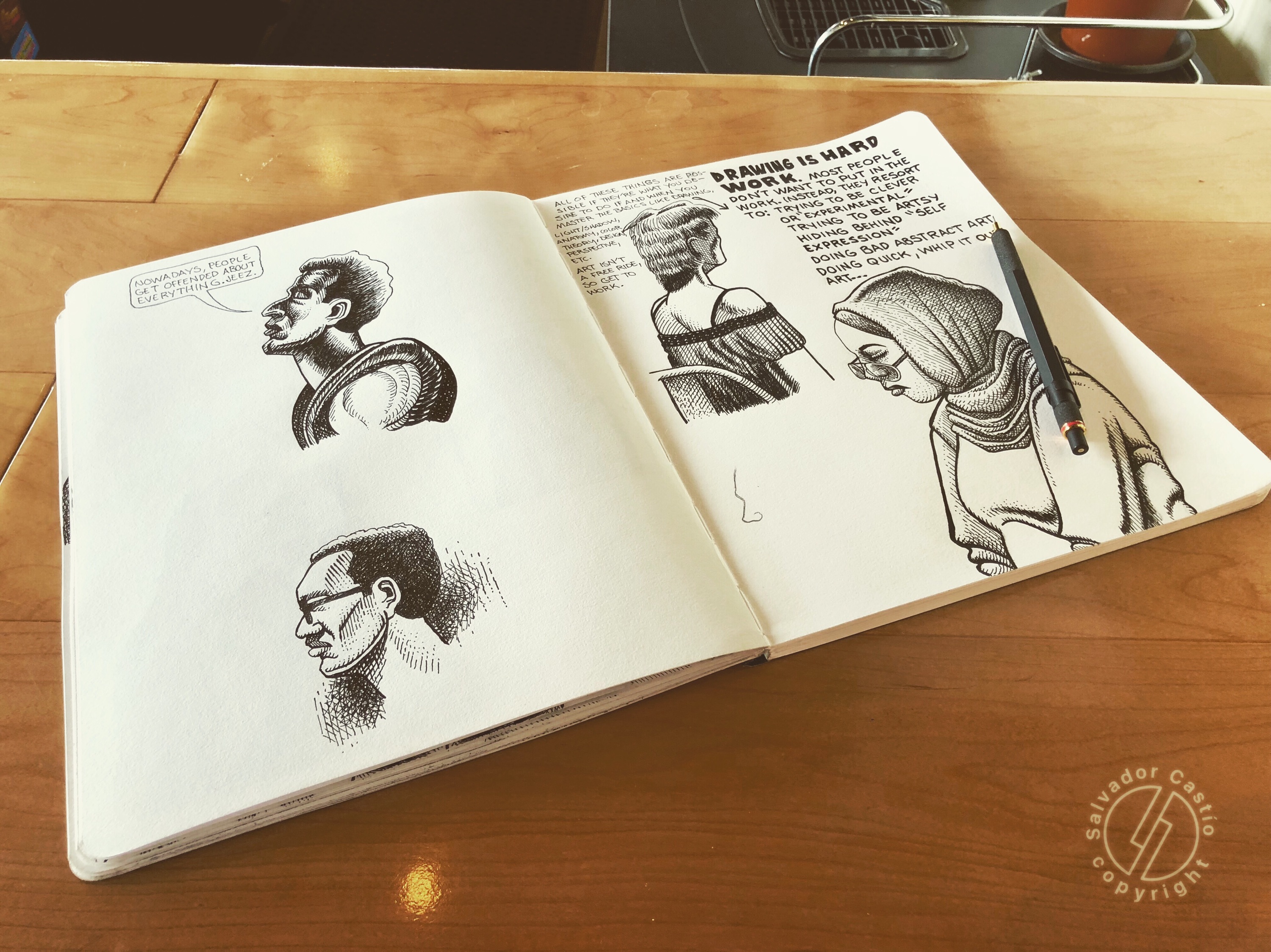

In addition to the cost of my labor, I always insist on using the highest quality professional-grade materials available. The longevity of my work is important to me. It makes no sense to invest so much effort into something if it’s not going to last. The paper I use for finished ink work is 3-ply Bristol board, which is entirely archival and of one hundred percent rag content, unlike cheaper papers made of wood pulp. The drawing inks I use, Koh-I-Noor Universal and Pelikan Schwarz, are waterproof and archival. My finished drawing of the Duchess is on a 10″x 14″ sheet of Strathmore series 500 Bristol board. My portrait of the duchess is drawn in pen and ink using a technical drawing pen, and it has small touches of Winsor Newton Designer’s white gouache, an opaque watercolor that I’ve used to make corrections. I usually do studies for in-progress work in my studio journal and then transfer the finished idea to my sheet of Bristol board. My studio journal is invaluable to me; I use it to work out ideas for upcoming projects. Its pages are filled with thumbnails, sketches, smaller studies, and technique roughs that will all assist me in realizing finished projects. My final portrait of the duchess benefits from this tried and true technique that I have perfected over the last three decades.

Finally, the most crucial component of my pricing is quality. Nothing speaks more loudly or clearly than finely crafted work. Beautiful art is the result of hard work, knowledge, and experience. When you buy a piece of work from me, you’re not only paying me for my time and materials – you are also paying for all the years that have come before that allow me to make what I do. It’s not something that happened overnight or something that’s come about by hippy-dippy magic. The price I put on my work isn’t about ego – it’s about thirty-five years of education, knowledge, and experience. Decades of effort do not carry a cheap price. If I ask you for twelve hundred dollars for a piece of work, it’s because I believe it to be worth that much. My work is excellent because I have refined my talent and skill to an exceptional level through years of hard work. There is no hyperbole in this – I have slowly elaborated and refined my talent and skill over decades in anonymity. My work tells the whole story at a glance; none of what I do would be possible without the struggle that came before.

Creating art isn’t just about technique and materials – it’s about much more. It’s about the life experiences that an artist has lived through that give their work depth and help communicate the pathos and gravitas of their story. These things factor heavily into the price of original art. A close look at the surface of any professional’s work will show you all the experiences the artist has lived through to create their work. It’s all there – every mark and trace of pentimento is part of the artist’s story. I hope these details have given you a greater understanding of pricing. I have the utmost faith that you, my dear readers, will consider my words the next time you ask an artist, “Why is your work so expensive?”