The terms “Starving artist and “Famous after death” have never sat well with me. They’ve always struck me as being simplistic and condescending. People who toss around these dimwitted epithets do so with an air of derision and a sense of warped frivolity. It’s all a big joke to them. They don’t care. First, they insult you, and then they proceed to ask, “By the way, can I talk to you about designing a free logo? Helen Miren famously said that she would advise her younger self to use the words “Fuck off” more often. At fifty-five, I have learned that lesson. Being blunt and to the point is also a fine art – you have to know when to land your punch. Don’t get me wrong, some people genuinely love, understand, and value what people like myself do. Unfortunately, they are few and far between. Regrettably, they’re not who I encounter most often. Usually, it’s people from the other faction that I run into, the people who dub everyone an artist and attempt to get cheap work out of them.

In all my years of making art, there’s one thing that has become more than clear to me: it’s not skill or talent that most people value. It’s the price tag that’s attached to your work. The bigger, the better. A little fame doesn’t hurt either. The mighty dollar and notoriety are a potent narcotic cocktail and aphrodisiac to most people. One drink, and suddenly you’re the toast of the town; people want to be around you, have you at their parties, and take you to dinner. Some people think that crack or meth is a big problem; trust me, crack and meth have nothing on money, greed, and power. It’s why terms like “Supporter of the arts” are dubious at best. I know people I would consider actual supporters of the arts – they’re a precious handful. They buy art, and they pay full price. It’s a glorious thing. Most would-be supporters of the arts are nothing more than hypocrites who can’t differentiate between Michelangelo and Charles Schultz and who insist on giving their money to people like Denzel Washington. They haven’t figured out that Denzel Washington doesn’t need their money.

Thanks to social media, we’ve reached a point where anyone can hawk their wares to whoever is willing to buy them. There are advantages and disadvantages to that: on the one hand. It allows any hardworking artist to get his work seen by the public, and that’s fabulous. On the other hand, it won’t be long before drunken monkeys make art and proclaim, “I got prints.” Platforms such as Instagram have become virtual flea markets for art. Every Tom, Dick, or Harry with even the slightest inclination towards making art is there, prints in hand. Do you laugh, or do you cry? I don’t know. This phenomenon is rooted in the lack of art education in our schools, amongst other things. If you do not understand the amount of work an artist puts into refining a skill, how can you value them? Artbooks and museum visits are nice, but that’s just the surface of it, not the guts. If you happen to know someone who makes art professionally, talk to them and ask them about what’s it like to make art. I guarantee that what you hear is going to be different from what you think.

With the advent of social media and smartphones, people’s perceptions of art have changed a lot. Frankly, it’s not just in the visual arts where you see this change. You see it all over the place. In a nutshell, in regards to visual art, it boils down to this: if you can fling paint at a canvas, then you are an artist. It doesn’t matter whether you have a skill or not, just as long as you can soak that canvass with blobs of paint. You may be wondering why something like this would interest me. It’s simple: it’s because “Anyone can be an artist” sends the wrong message to people about what artists do. To be clear, when I say artists, I am referring to professionals -not hobbyists or people who do it as a side hustle. I’m talking about the people who make art day in and day out for a living. Let me be clear about this, I will always stand up for the people who have spent their lives busting their asses to elaborate skill and refine it to a high level. Refining skill requires a certain level of commitment. It’s a level of commitment that most people aren’t willing to make.

Making art isn’t a free ride. Artists spend copious amounts of time learning their craft because it’s important to them. It’s not a hobby – it’s their livelihood. Attempting to devalue or minimize that in any way will never sit well with me. If you think anybody can be an artist, I cordially invite you to pick up a pencil and take a whack at elaborating actual real skill. Instead of pushing the notion that everyone can be an artist, we should present the idea that being an artist requires as much work as anything else and that hard dedicated effort pays off. Trivializing what artists do is insulting and helps nothing.

Some people ask, “Why is your work so expensive?” It’s not – not by a long shot. If your idea of expensive art is twenty-dollar paintings seen at the flea market, then I’m the motherfucking Louvre. The price that I place on my original work isn’t something I’ve arrived at willy-nilly. Besides the cost of my materials, my education, knowledge, years of experience, and skill level all determine the price of my work. Is it expensive, perhaps? Is it fair? It absolutely is. I’m often gobsmacked by how little the general public understands such things. When you buy work from me, you’re getting art created with skills perfected over decades. Beyond that, you’re getting something that is unique, and that has singular value.

The surface of my work is alive with human involvement and thought. The image I’ve brought forth results from a long series of decisions – I have thought about every detail. I do this over and over until I am satisfied with my composition. All my choices are evident on the surface of the original you buy from me. In the digital age, you don’t have that tactile dimension. Instead, you have things like the newly minted NFTs that people use to validate ownership of digital files. I skeptically watch at a distance as people pay exorbitant amounts of money for the right to be declared the official owner of a digital file. A digital file is not an original piece of work. You cannot touch its surface and feel the paint or ink with your fingertips. In my era, you had copyright – artists still have copyright. It’s something that happens automatically upon completion of a work of visual art. If someone wants to own the copyright in addition to owning my original, they will pay for a complete buyout upon purchase. Desiring this can often triple the price of a piece of work; hey, if you want my copyright and the bragging rights of being the owner of my original, then you’re going to have to pay steeply for it.

As you can see, all kinds of things are happening when it comes to making art. More than ever, artists must know who they are and what type of work they want to do. They should have a reason for making art beyond making money, creating a product, or creating content. Along with a strong sense of self, they should also have a robust set of skills that they have mastered. If you can go to art school, go. If the school is in a major city, you’ll also get an education outside the classroom. Experiencing culture firsthand is one of the best things that you can do. Growing as a person is just as essential as growing as an artist. Learning from the best in your field of study will advance your skills by leaps and bounds. There’s nothing like in-person technique demonstrations.

I know, I know, art school isn’t affordable for everyone. I get it; it’s expensive – more now than ever. There are other alternatives: community colleges seem to offer a much higher level of education in the visual arts than in the past. You can save money by starting there and then transferring. You can also choose to be an autodidact. This route is much trickier as it requires double the drive you usually need to become a professional. If you’re hell-bent on succeeding, you can do it, but those who triumph by taking this route are the exception, not the rule. Lastly, there are online courses and YouTube. Choosing this would be my last choice unless you’re already a professional with experience. If you’re a novice who’s just beginning, I would be aware. You can teach certain basics via video, but that’s limited. You cannot learn to draw the human figure on a computer – you have to be there; otherwise, it doesn’t work. Lastly, teaching art via video has become a cottage industry where any Joe Blow can proclaim to be an artist. If you’re not careful, these slick, wheeler dealers will reel you in and take your money. If the person teaching me isn’t solid in basic skills like drawing and painting, why would I want them to teach me? If you’re a hobbyist, these types of things could be beneficial, but if you’re serious-minded and wish to become a professional, I urge you to sign up at your local community college. The worst thing you can be as an artist is ignorant. Master the basics, learn about the history of your particular discipline, and understand where you come from and what you’re doing. Above all, realize that making art professionally is no free ride. You either put the work in, or you don’t. Finally, stay away from people that believe that everyone can be an artist. They’ll never truly value your work.

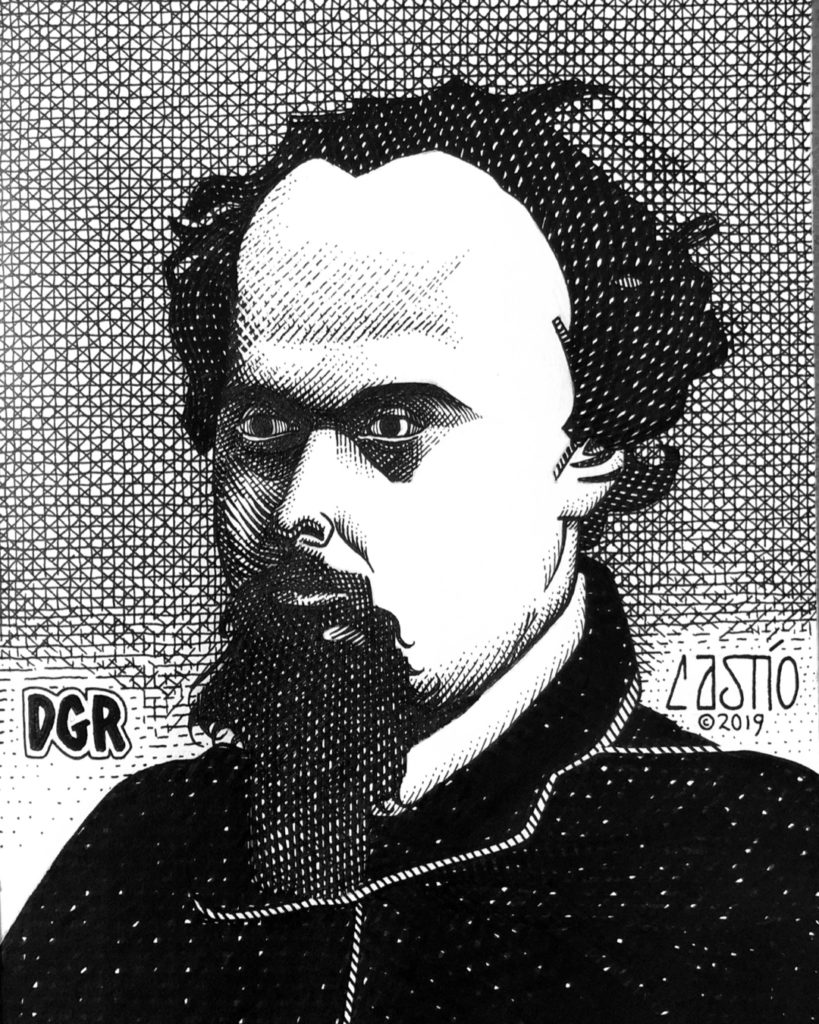

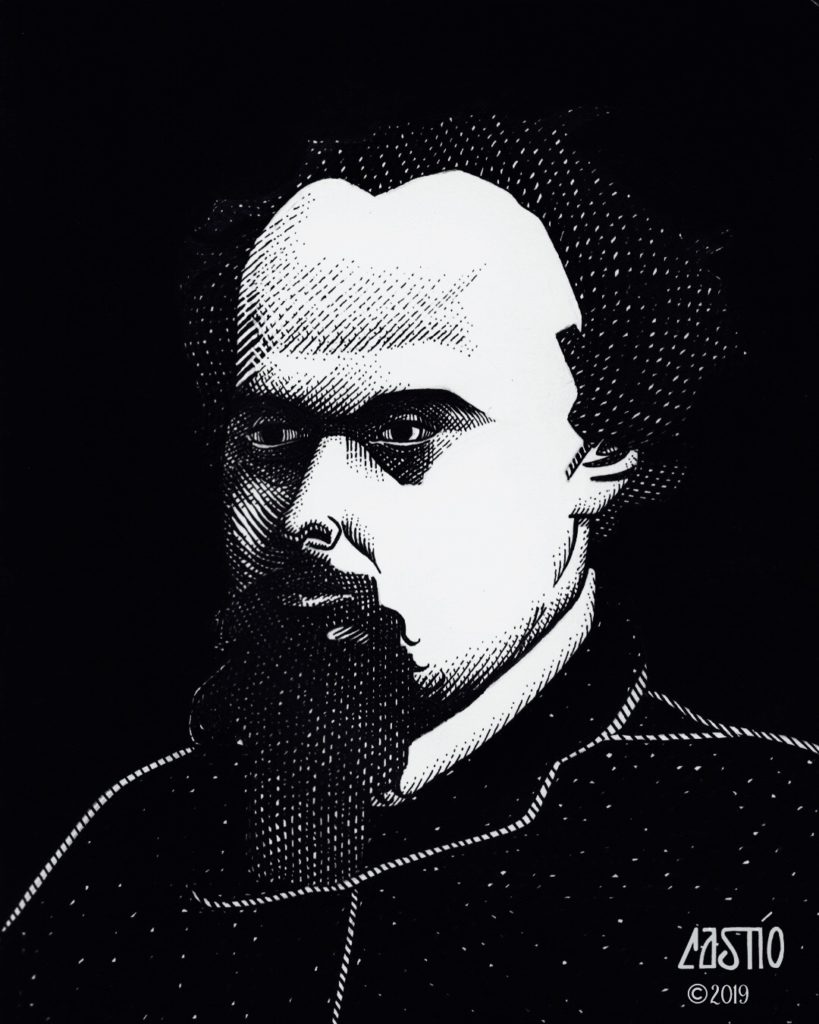

Illustrations used in this blog post.

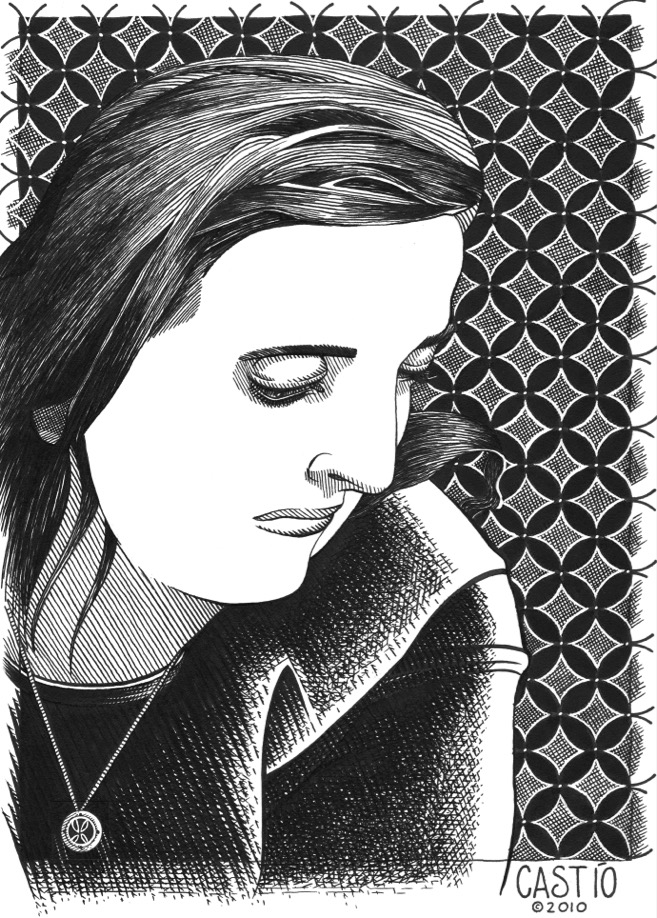

Renee. 2010. approx 9’X12″. Pencil, pen, ink, and gouache on paper.

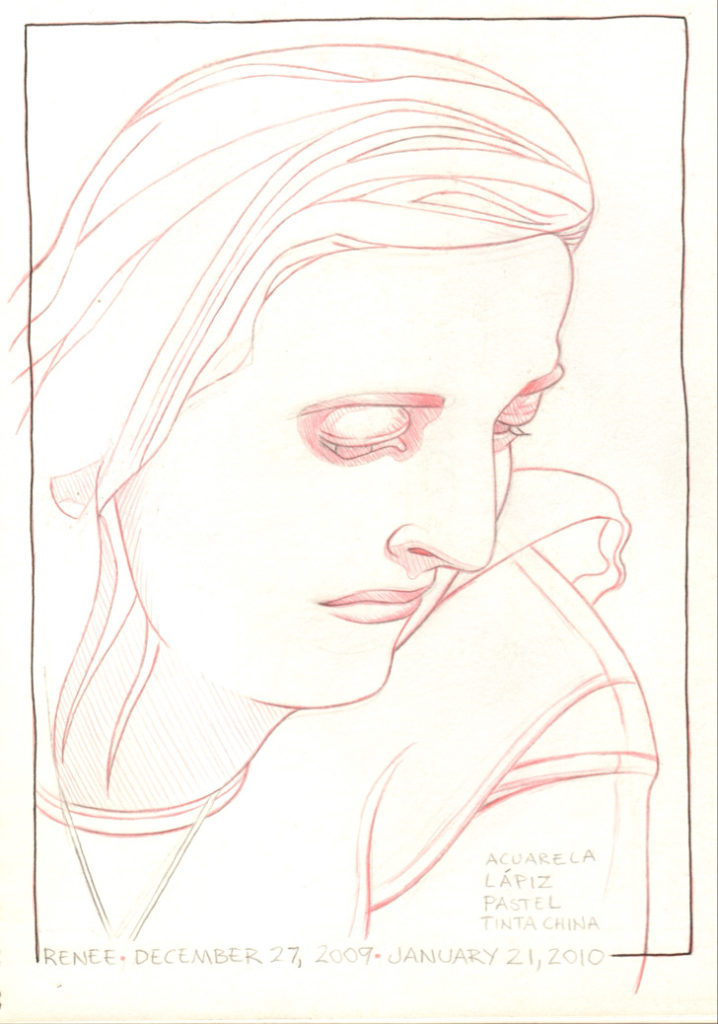

- I love drawing portraits that reveal something about the subject of the drawing – a small personal detail that adds a deeper level to the artwork. My friend Renee has unique features that I felt would make a wonderful drawing. She graciously agreed to pose for a series of pictures that I snapped while visiting family in Southern California. As always, I take numerous shots so that I can cherry-pick the best ones. It’s not too hard to find good shots when you have someone with wonderful features like Renee. As I snapped my photos and we chatted, she told me that she was of Indonesian descent. I was automatically intrigued and wanted to find a way to convey that fact in my drawing. Anyway, I started with a preliminary done in red pencil. At the time, I thought that using a color underneath my inkwork might give it a little more depth, but for some reason, I didn’t follow through with my idea. I honestly don’t remember why, but maybe I’ll go back and give it a shot.

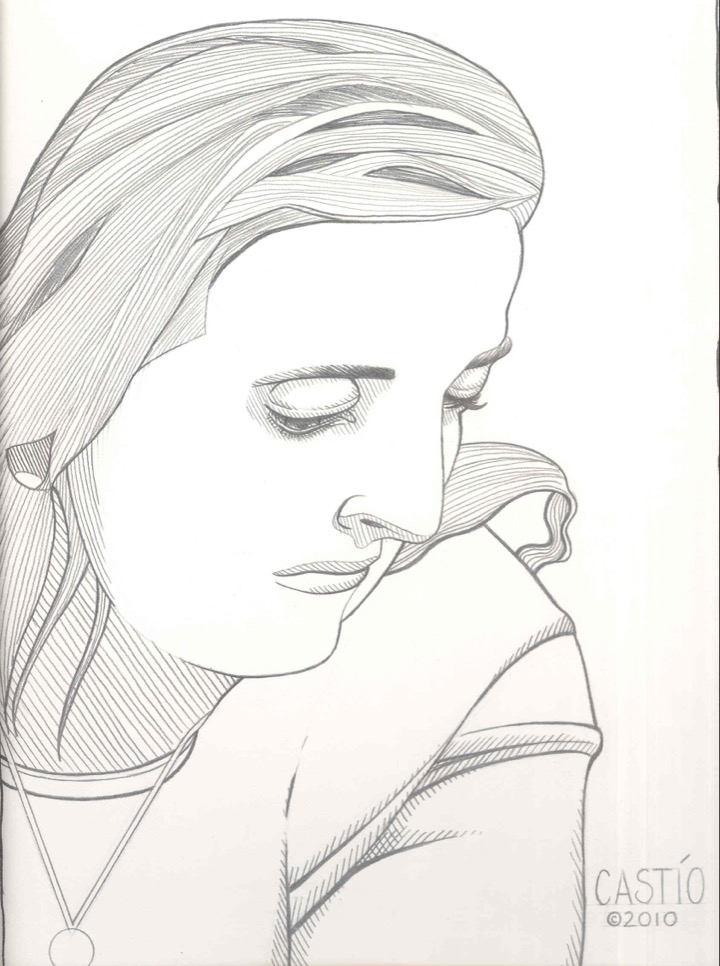

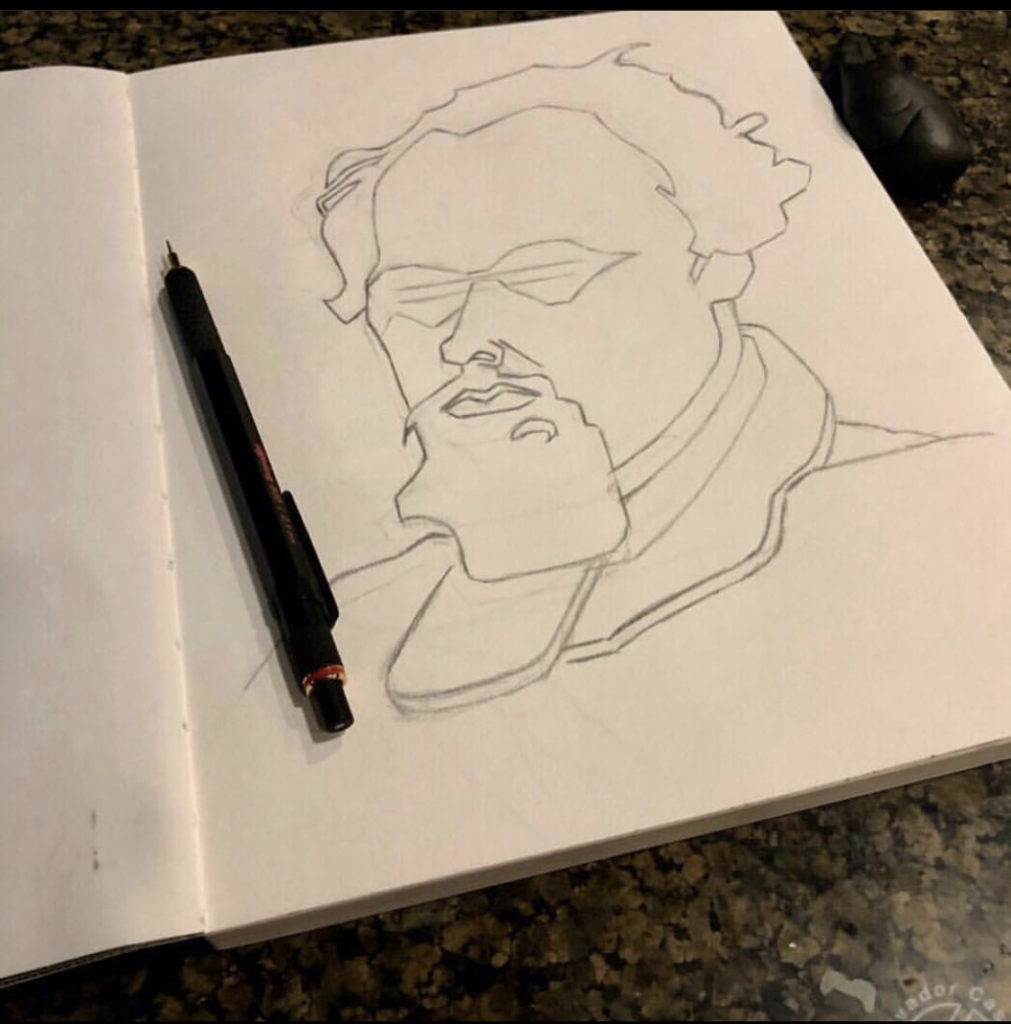

- The most important thing to me at the beginning of any drawing is getting a solid pencil preliminary done. I cannot emphasize enough how important it is to do this as you begin your drawing. Everything has to be worked out at this stage: proportions, facial features, likeness, details such as hair, etcetera. If these things are not worked out here, you risk making time-wasting mistakes later on. At this stage, I was still trying to figure out how to incorporate my friend’s Indonesian heritage into my design.

- Here you have the finished article. As you can see, I incorporated a repeating Indonesian pattern in the background. It was this detail that brought everything together for me. I’m well pleased with my drawing; without it, it would be just another nice pen and ink drawing that says nothing. Interestingly, my desire to give my portraits personal depth has not ceased since I did this drawing; instead, it has increased. I find myself more interested than ever in doing drawings that reveal personal stories.