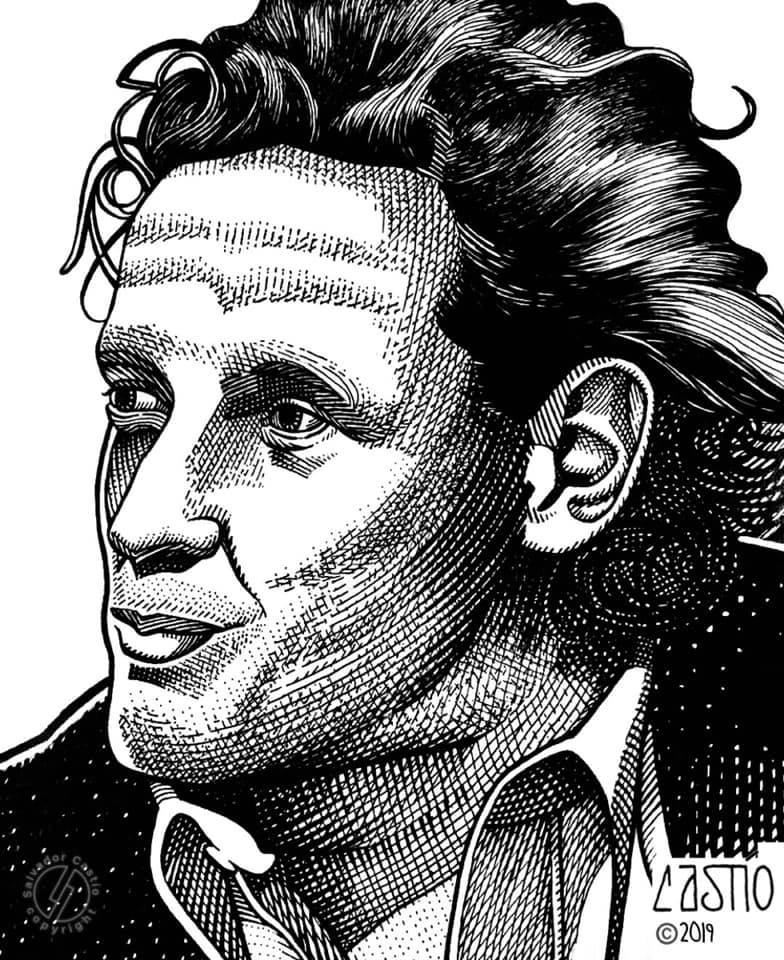

No one could be more different from me than Marco Pierre White. I’m an American – he’s English. I’m a visual artist – he’s a chef. I’m chill – he’s volatile. Despite these differences, reading his autobiography, The Devil in the Kitchen: Sex, Pain, Madness, and the Making of a Great Chef, has both inspired me and spoken to me both viscerally and intellectually.

This is not the first time that I have found commonality with people that seem very different from me; despite our differences, and sometimes because of them, these people have often served as guiding lights and I have seen them as kindred spirits. As a teenager I discovered the work of Pre-Raphaelite painter, Sir Edward Burne-Jones. Despite the cultural differences between us, I found much in common with Burne-Jones: he was also an only child from humble beginnings who used art to better himself. I also connected with people such as French comics artist Jean Giraud: again, he was an only child, his biological father was absent in his life, his grandparents helped raise him, and he used his art to navigate through childhood. These are just two individuals among many others that I’ve felt an affinity with. I feel a strong kinship with these people because the fight for excellence knows no boundaries: cultural, geographical, or other differences do not matter whatsoever.

As a draftsman, storyteller, and picture maker, I’ve drawn most of my inspiration from visual artists: painters, illustrators, comic book artists, and the like. In addition, I’ve also drawn inspiration from musicians, writers, directors, etc both foreign and domestic. No matter the discipline, the one common denominator that’s always inspired me is excellence. My reverence for excellence is what led me to discover Marco, a British chef and culinary hero who’s famous for being the first and youngest English chef to win three Michelin stars.

Marco’s book showed me that the struggle to succeed as an artist is also the same struggle that one faces on the road to becoming a great chef: it’s all or nothing. You either do it right or you don’t do it all — there is no in between. I found the same relentless, hell-bent attitude that exists in my life on the pages of Marco’s book. It’s always comforting when you find another person whose bloody mindedness is the same as your own. Perhaps the one thing that struck me the most while reading The Devil In The Kitchen was that beyond all the kitchen staff bollockings, service meltdowns, cheese-flinging episodes and notoriety there was a deeply profound belief in himself and his abilities. Things like that always speak to me. It’s the common thread that binds me with every single person that has inspired me along the way. Again, the fight for excellence unites me with this brotherhood of people who are driven by a singular and profound belief in themselves. Despite our differences, we are the same.

Craft and Substance

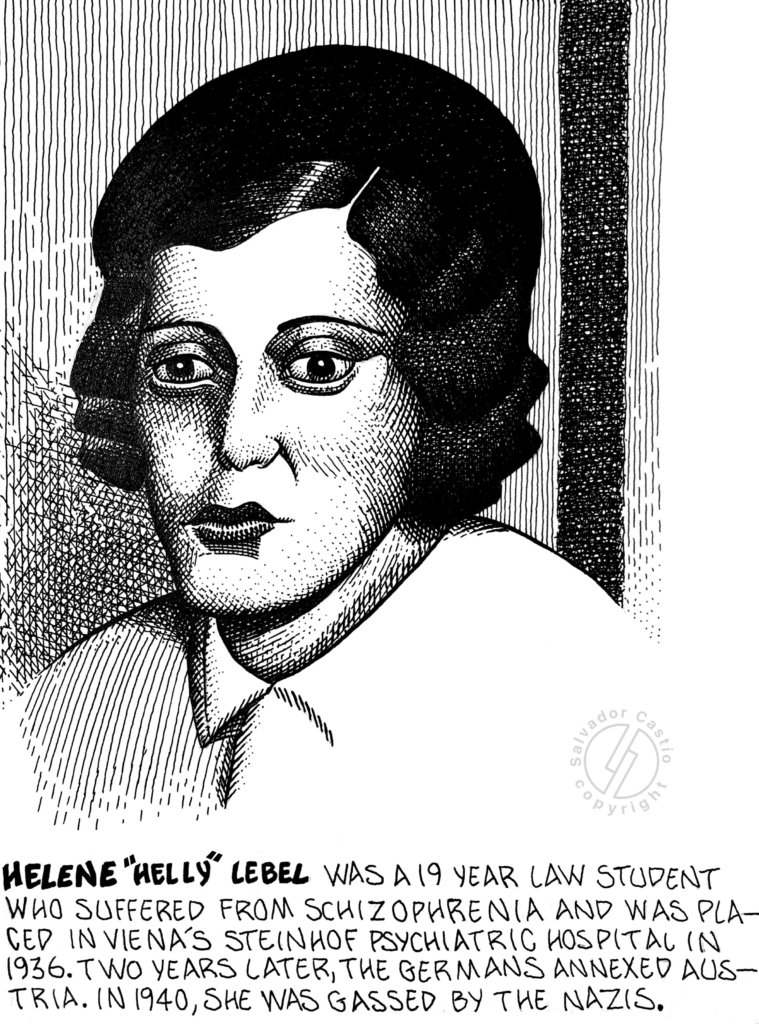

After my last blog post, I realized that there are two things that it boils down to when making art for me: craft and substance. I’m at an age where certain things need to be inherent in whatever I create: It must be well designed and it must be well crafted. I’m not a fan of bad art. I loathe it; I loathe it even more if I’m the one producing it. In my eyes, there’s no excuse for mediocrity. None. You either do it right or you don’t do it at all. Facility and great technique can certainly be impressive, but they alone are not enough. The piece of work being created has to say something about me as a person — it has to have substance to it. It doesn’t matter if it’s going to hang on a gallery wall or if it’s going to be in my sketchbook — the work has to reflect some aspect of me as an individual and my POV on the world at large, or whatever. Otherwise, what’s the point? The drawing that adorns this week’s post is a fine example of what I’m talking about.

When I read the story of Helene Lebel, it struck a chord deep within me. In my life, I’ve encountered and witnessed up close what the effects of mental illness do to people. On a personal level, I watched as my uncle, Raul, struggled valiantly with schizophrenia for over 30 years. It’s a horrible thing to watch – physically, my uncle appeared to be well but his appearance belied the internal chaos and the forces that were mentally ravaging him. I also witnessed the scourge of mental illness as part of a job I held. Years ago, I worked as a Spanish mental health interpreter for San Joaquin County; on a daily basis I, once again, got to see the insidious effects of mental illness at work. Along with the doctor or therapist and the client, I was present during appointments. This meant that I heard everything that was said during the appointment. Sometimes, I wish that I’d never heard some of the things that were discussed during those appointments. Interpreting at the clinic for adults was bad enough, but interpreting for the children’s clinic was heartbreaking.

Sadly, in 2018, mental health still carries a stigma. People who suffer with mental health issues are still described as being: crazy, nuts, cuckoo, whacked, touched, bat-shit crazy, etc. It’s so unfair to label people like that — they can’t help it. I often wonder if the people who make such remarks about complete strangers would do the same for someone they love? I’ve learned that everything changes when an issue becomes personal. Funny that. After my experience with mental illness, and based on what I’ve seen and heard, I wouldn’t wish mental illness on my worst enemy.

Helene Lebel’s story is tragic. At age 19, when she was a law student, she began to show symptoms of schizophrenia, and was forced to abandon her studies. In 1936 she was diagnosed with schizophrenia and placed in Vienna’s Steinhof Psychiatric Hospital. Two years later, the Germans annexed Austria. Helene’s parents were made to believe that she was going to be released, but that was never going to happen. In August 1940, Helene’s mother was notified that Helene had been transferred to a hospital in Bavaria, when in reality she had been transferred to a converted prison in Brandenburg, Germany. There, she was subjected to a physical examination and then lead into a shower room. Helene was one of 9,772 persons who were gassed at the Brandenburg Euthanasia Center. She was listed in official paperwork as having died in her room from “acute schizophrenic excitement.”

I would like to thank the US Holocaust Memorial Museum for providing information and details on Helene’s life.